Sheep Fertility, Genetics or Management - The Booroola Story

- ASHEEP

- Jun 23, 2020

- 5 min read

Updated: Feb 25, 2022

Article by Bob Reed, ASHEEP Committee Member, sharing his thoughts and knowledge of the Booroola story.

In 2007, on our second ASHEEP trip to the South Island of New Zealand, we got to spend half a day with the scientists at the Inverdale site of the Dunedin University. These were the people who had relatively recently cracked the full sheep genome, the first people in the world to do it. They had already established three gene markers, one of which was a fertility gene the Inverdale gene, which gave a 25% lift in lambs on the first cross. Unfortunately, when ewe lamb progeny from the first cross (i.e. maiden ewes carrying the Inverdale gene) were mated to the same rams the lambing outcome became recessive. Basically they could lock in the 25% but they couldn't add to it.

The above was early days with sheep genetics but it was great for us to revisit them in 2017 and see that they had maintained their passion for quality genetic research and development.

Now we are told that fertility in sheep has a relatively low rate of heritability and lambing outcomes are mostly down to management and nutrition. Is that necessarily so and does the breeding history of the Austrailian Merino tell us that? Not necessarily so. When farmers are making real progress with lifting twinning rates we need to hear what they are saying and what they are saying might sound a bit like this -

"I don't like to say twinning is highly heritable, but that with proper care, it is highly repeatable."

The Booroola story is not necessarily well known but it has always fascinated me. I cannot understand why more wasn't done with these sheep when they went to the CSIRO and Trangie in 1960. I can only speculate that it was all about wool in that era when farmers and pastoralists were happy with enough lambs to provide replacements and a bit of room for classing. Australia's average lambing percentage was under 70% and yet many in the industry couldn't get excited by 200%!

Be it as it may, here is the Booroola story as I understand it.

The Booroola Story

The Booroola strain of merino was developed by members of the Seears families in the Cooma district of NSW. This Booroola strain was a unique development for it represented a very definite genetic entity of extremely high fertility, evolved and fixed by two generations of commercial breeders on adjoining properties between 1916 and 1960.

The originator, Bert Seears, began selecting sheep on multiple births when he segregated a ewe that had experienced repeated multiple births and bred on from her and her progeny alone in a separated flock. By the 1930s, Seears had a number of ewes regularly producing triplets and quads. One ewe gave birth to 27 lambs in her lifetime and another (named Incubator!) once had seven lambs in a litter.

Apparently Bert spent most of his days fostering these lambs onto surrogate mothers to preserve their unique genetics. His own ram replacements were bred from within this closed flock.

In 1945, Bert gave two of his precious high-fertility ewes to his nephews Jack and Dick Seears who became devoted to continue the work commenced by Bert. They did however vary the mating procedures by using Egelabra rams on the separated and growing flock of their own and also spent most of their days fostering progeny. Obviously the Egelabra influence did not wash out all of the fecundity of this

ongoing Booroola flock as by 1960 their special ewe flock of 232 ewes, directly descended from the two ewes given by Bert 15 years earlier, were still lambing over 200%.

Effectively, the Seears families had isolated, concentrated and perpetuated a major gene function which had been discarded by long past merino breeders. By this stage the CSIRO had begun research into twinning at Deniliquin and had acquired some ewes from the Seears brothers and went on after the Seears' deaths to aquire around half the Seeras flock. Likewise the NSW Department of Agriculture took on the other half of the flock at the Trangie Research Station.

Ultimately, it was the CSIRO via the recognition by some scientists (particularly Dr Helen Newton Turner) that the high fertility of the Seears flock was not a genetic mutation but instead probably traced back to the highly fecund Bengal sheep brought into Australia in the early days of the colony. These sheep, primarily brought in for rations, were also bred from and eventually crossed to Merino rams in John

Macarthur's time (1800-1820). Early historic colony references point to the Bengal sheep having high levels of multiple births.

These Bengal sheep were also small and scrawny which probably led to later sheep classers heavily culling their crosses and throwbacks.

Luckily, some 100 years later, this fertility gene was found at Cooma and valued for its potential in future breeding programs. The Trangie Booroola remnants eventually came to WA where Dr Don Robertson ran them on a small farm at Gidgegannup. Don was lecturing at Muresk at the time and fully appreciated their background and genetic value. I was lucky enough to visit his farm in 1977 and Don kindly ran through their history for me. They certainly were fairly small sheep but robust and were lambing at the time, plenty of multiples as I recall.

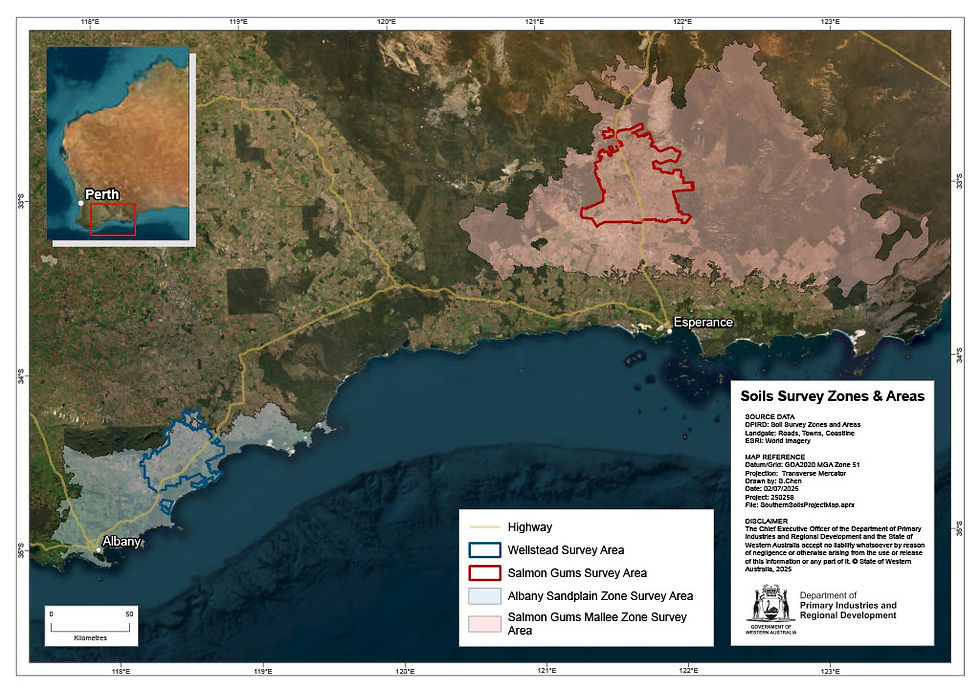

In later times, 1996, I visited the Trangie Research Station with a few of the old Esperance Rural Properties team. We saw their high fecundity flock which carried Booroola input from earlier times mixed with a lot of other genetics. I didn't think this project was still a high priority for them. I understand the CSIRO flock got shifted to Armidale (NSW). The last known sources of Booroola genetics known to me were Don Robertson and CSIRO Armidale but that's all a long time ago now.

I can remember talking to Mike Overhue about Booroola in my early days at Esperance. I know he aquired some stock from Don Robertson but I don't know where it went from there.

However, we now know 100 years of backcrossing Macarthur's initial Bengal / Merino to Merino couldn't fully remove the Bengals fertility gene. We also know that Jack and Dick's special flock were still lambing at or above 200% after being continuously mated for 15 years to Egelabra rams up to 1960 - 140 years after Macarthur. One would hope we have't lost touch with the Booroola genetics after all the work those Cooma Cockies did the hard way.

And it wasn't only the Bengal influence that got into the Australian Merino. As they pushed sheep further west, into the drier Riverina and beyond, Macarthur's small merinos lacked the constitution to handle the environment. Astute SA and Riverina breeders began to add, after 1850, large framed long stapled English Leicester and Lincoln blood to their breeding mix. These genetics, after backcrossing back to

the merino, supercharged the Australian Merino in respect to size, staple length, wool cut and constitution.

In conclusion, the modern Australian Merino is not the pure aristocrat it is put up to be and it's all the better for it. There have been many and varied genetic introductions along the way leaving traits which could still be retrievable. Better genetic fertility could still be a prize?

Bob Reed

References: Charles Massy, 'The Australian Merino', Dr Don Robertson